The end of the world starts small—it could be a handful of dried goji berries

or marginalia left by the previous reader of the ‘Homo Faber’ you just bought

at a stall—yet apocalyptic eschatology focusses on a grand finale of a sort,

even though the whole world comes down to a few stanzas on a tarnished page

trapped in the typewriter perched on a battered desk in your attic studio.

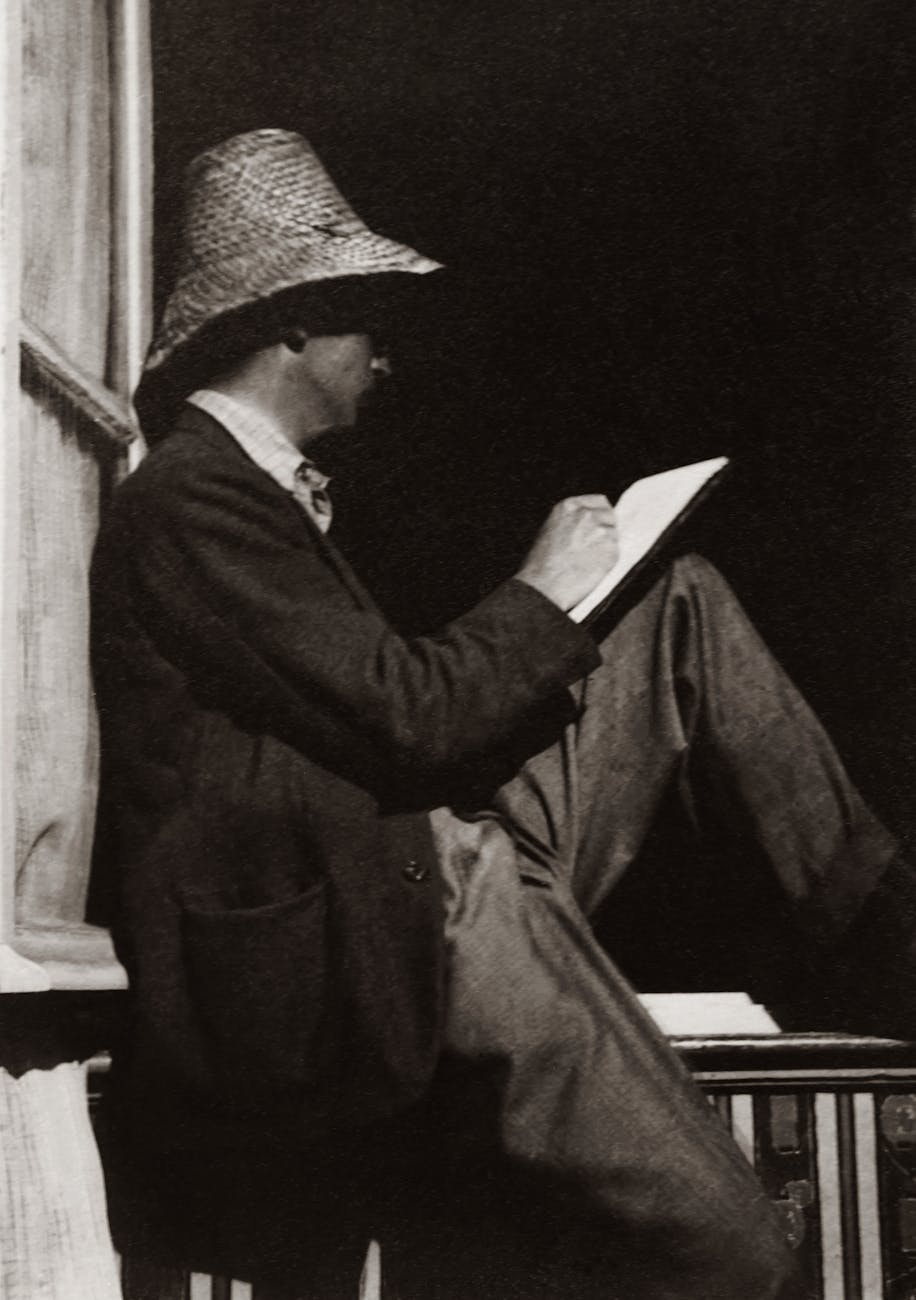

Tag: poet

What does it mean to be a poet?

What is the worth of mere words, if their true meanings make no difference to what a man does?

The Good Book. Parables. 11:7. Made by A. C. Grayling (2016)

Sometimes I wonder if I’m still capable of expressing a genuine, unadulterated awe

like my daughter does. It’s like facing Wendy Beckett—whom I enjoyed watching

wander through the world’s greatest museums and art galleries, but whose attire

always left an unpleasant aftertaste on me—when the hours of my youth are no more,

and so is my conviction, yet I cling to the mores that the social inertia has instilled in me.

Perhaps that’s exactly what it means to be a poet.

This is not a poem

For R. Mutt

This is a poem,

if I so decide. I have the power to do this.

After all, I am a poet and a seasoned connoisseur

of porcelain fixtures.

One of the myriad

Writing poetry has always been a peculiar occupation,

even more so now, in the Age of Imagination,

when it has turned from the spiritual torment of a few under patrician patronage

to a thankless endeavour pursued by the faceless myriad, hardly ever paid for,

even in that cheap currency called likes, driven by some obscure algorithm

that decides whether and to whom to show your stanzas.

What I’m actually trying to say is that I’m a pathetic third-rater,

feeling sorry for myself because no one reads me

—except you, of course.

A fig leaf

I spent this morning reading my own poetry,

which I haven’t done in a long time,

and I found it not bad—not bad at all.

In fact, it’s quite good, if I do say so myself.

Yet hardly anyone knows it, and what’s more,

I’ve wasted any chance to get it published

by simply posting it in that petty cubbyhole called the Web,

or so the experts in the field say.

The above may sound somewhat conceited,

but—though it comes at a price, as there are no free meals

in this corner greasy spoon—isn’t being bold a poet’s birthright?

If I didn’t know any better, I’d be inclined to believe

that every artist is actually a bit of a smug,

condescending arsehole doomed to sainthood

—a fig leaf covering up everyone else’s free pass

to continue business as usual.

Random thoughts swirling through the poet’s mind after waking up

For millennia, people thought

that the sun revolved around the earth,

and it took a great deal of ingenuity,

pursued by burning at the stake,

to mentally set foot on the former,

or rather beyond both celestial bodies.

And yet we still have ardent flat-earthers among us.

After only a few miles on the bike,

a well-oxygenated brain may absorb a fair dose

of Wittgenstein or decide to leave the typical nine-to-five

for something more exotic, like a snake milker,

a ravenmaster, or a professional mourner.

If you are particularly lucky, you might even land your dream job

as an eternal employee, although that would require moving

to Gothenburg in Sweden.

My father used to say, ‘Ordnung muss sein,’

so that I would know that bending over a stool

and counting aloud the blows with his army belt

was for my future good;

otherwise, I could mistake it for an act of cruelty.

I wonder what his views would be

if he lived to see today, when even a light smack

is a criminal offence.

Journal (The sound of the waves)

What do you do when you realise you are not going to be a great poet one day? After thirty years of writing poetry, you finally give up, make a note of it in your journal, and move on. Simple as that. After all, there is more to life than putting together a stanza, even a great one. And if, in your case, it’s decent at best, what’s the point? Instead of wasting hours in your room trying to find the right onomatopoeia, wouldn’t it be better to listen to the sound of the waves while walking on the beach?

Journal (Bright but lazy)

My education is quite a complicated story. Bright but lazy was the general opinion teachers had about me when I was still in primary school. It’s not that I couldn’t have done more in terms of my academic achievements—I learned all of seventh-grade maths in one weekend to prepare for the end-of-year exam, scoring better than the model student in our class—but it just never really interested me. I preferred to immerse myself in the world of literature. At that time, reading books bordered on obsession. The book was the first thing I took in my hands after waking up. I ate while reading, I walked to school with a book in front of my face (I’m still surprised I was never hit by a car), and in class I read with a book on my lap under the desk so the teacher wouldn’t catch me. Books filled the rest of my day after school, and when my parents finally turned off the light in the middle of the night, I stood behind the curtain and read by the light of the street lamp in front of my room window.

This situation continued throughout my entire education, abruptly interrupted when I failed one of my final exams, and instead of going to university to study philosophy, I ended up in the army. I passed the exams eventually after quitting the army, but at that time, the reality of adult life hit, and I had to find a job.

A few years later, after saving some money, I started a part-time study at Jagiellonian University, the oldest and one of the best universities in the country. I studied the cultures of ancient Rome and Greece, but after a year, my finances did not allow me to continue. My father lent me some money, but this time I decided to be more practical and switched to political science with journalism at my local university. It made more sense because, at that time, I was already working for the largest daily newspaper in the region, and half of my colleagues were studying there. Unfortunately, I devote more attention to work than to studies, and I failed the year. And that was it. Only a few years later, I returned to Jagiellonian University to study comparative literature as an aspiring poet, but again, it turned out to be just another one-year stint.

It required hitting the brutal reality of immigrant life and six years of hard work studying while in a full-time job for me to actually get a university degree. But even that wasn’t without some turmoil, as I started in mathematics and statistics just to switch after two years to computer science. But in the end, I finished it. The odd thing is, it stopped having any meaning for me. Perhaps because it happened at the same time as the breakdown of my marriage. But that’s a different story.

Addiction knows no glory

Whether I read The Waste Land or Metamorphoses,

Much Ado About Nothing or Waiting for Godot,

The Karamazov Brothers or One Hundred Years of Solitude,

I am constantly reminded that there is more to writing

than writing. And I know the so-called ten thousand-hour rule,

but I’m also painfully aware that even if I double or triple that,

I still won’t be even remotely close to Whitman or Keats,

regardless of whether it is a matter of a gift from some gods

I don’t believe in or genetics and the fact that my brain

may lack the unusual setup of Einstein’s. But despite everything,

I keep writing because what doesn’t go away with adolescent acne

becomes a lifelong addiction.