Nothing is real but reality in a watercolour

fog washed with the secretions of the graveyard

shift, like the yawner’s mention of a scarlet dawn.

Is it the fool moon mocking the street lamps

with reflected light that holds terror for one,

or is it the crunch of pebbles with each tired step?

And while the outline of meals has long lost its meaning,

they are still necessary to keep up appearances.

After all, any of them could be supper.

Tag: death

A rude awakening

In the river of yellow umbrellas,

the rain swims with frantic crawls,

as if plotting wet shoulders were barely enough.

But even if the sky forgives the reflection

and the wind forgets the manner,

once they learn that forever has a pretty short shelf life,

they will realise all that’s left is to count

the grains of sand stolen from an hourglass

and be cautious.

Journal (Standing next to the coffin)

Everyone’s going to die. It takes a philosopher or a desperate teenager to say this. Everyone else who should be able to address the topic is likely to ditch it. I’ve never understood why the subject of death is seen as depressing. Of course, there is nothing to celebrate for obvious reasons, but since death is an inevitable part of life, we should at least treat it with equanimity.

I remember when my father died. On the day of his funeral, my grandmother asked me to take a picture of her standing next to the coffin. At the time, I found her request absolutely bizarre. I’ve never been particularly fond of taking pictures in the first place, but such an occasion seemed even less suitable to capture in a photo. And yet here I was, satisfying her request as if we were at a family picnic, having fun. But maybe that was exactly the approach to death I have now. If we photograph birthdays, weddings, holiday trips, and every other event in our lives, then why not funerals? What’s so strange about that? After all, it’s just another life event.

My grandmother lived in a small village, far from any city, and I never perceived her as a philosophising type. The few memories I have of her are related to her work on the farm. Perhaps I should have talked to her more when I still had the chance. Who knows what I would have learned from her? It’s sad that we learn to appreciate people only when they are no longer with us.

Journal (A bowl of petunias)

Waking up in the middle of the night with a pain in my chest always reminds me of my mortality. It’s not like I think about death all the time, but touching on the subject with such an emphatic reminder is inevitable. At least I’m not superstitious like my father was, who, when asked about making a will in the face of cancer, became really upset, treating the suggestion as a wish for his death. But maybe I just had more time to get used to my condition. After all, I was born with it.

Perhaps it’s a lack of imagination on my part, but the idea of dying has never terrified me. And not because of my Catholic upbringing, with the morbid theatrics of Ash Wednesday and the promise of the resurrection of the dead that I never consciously believed in, not since I left the innocence of childhood. I simply find existence itself rather mundane and prefer to think of myself more as a bowl of petunias than a sperm whale, if I were to refer to Douglas Adams’s iconic The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

Journal (It’s not me—it’s the world)

Montaigne said that as our birth brought us the birth of all things, so in our death is the death of all things included. But with that in mind, why would I trouble myself with death if it’s not me who died—it’s the world that ceased to exist? And shouldn’t those rather laugh at the end of this spectacle who cried at the beginning, especially if they might have already outlived their purpose?

Here, in the Western world, death has a particularly bad press—if mentioned at all—but you can’t avoid it if you ask about a happy life, since, to follow Ovid in Metamorphoses, we should all look forward to our last day: no one can be called happy till he is dead and buried (from The Essays of Montaigne—Volume 03 by Michel de Montaigne, translated by Charles Cotton). But sometimes, just like everyone else, I ask myself: Was—or is, as I’m still alive—my life a happy one? The problem is, I’m not even sure what that actually means—a happy life. I would say adequate. It’s like the dust on my desk—sometimes I wipe it off, but most of the time I get along.

We value human life exactly because it’s so frail and because it eventually ends—because of death. What would happen to that respect once death was gone?

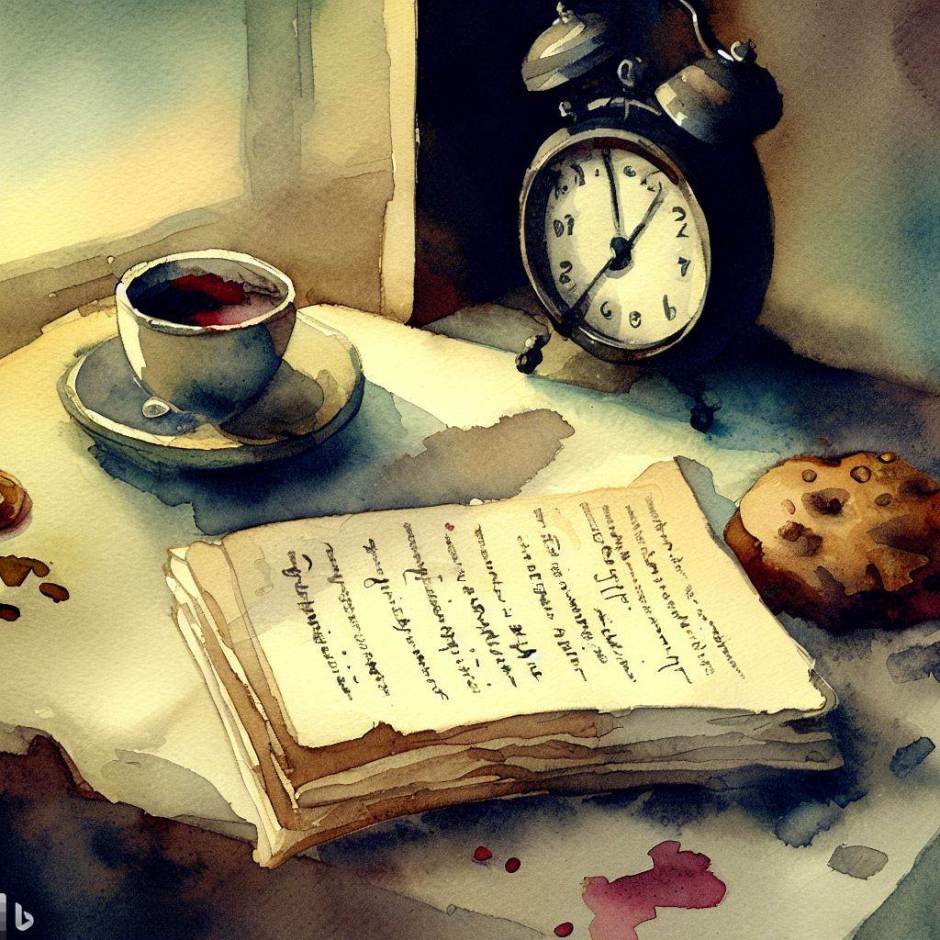

In the hour of my death

In the hour of my death, I did something insignificant,

as I often would. A book fell to the floor, bending the pages,

which I never liked. A stillborn note cut off mid-sentence

never got a chance to become a stanza. A cup of tea gone cold

and a half-eaten cookie—not even a madeleine—that at best

could remind someone of my cholesterol problems were waiting

to be thrown away. Only the clock, as always, marked the passing

moments with its regular tick-tock. In the hour of my death,

I did something insignificant because, in the end, I was taken

by surprise again.

Mind your words

We often say, I’m dying for this, or I’m dead serious about that, or even I would die

a thousand deaths before [something], not to mention the notorious dying of a broken

heart, but sooner or later death is going to be more than just another figure of speech.

Shadowing life like a stop-motion artist replacing figurines on a scene so that hardly

anyone notices frame skips, with a single casual stroke, it will stop you mid-sentence

for ever, regardless of whether you mind your words or not. But you could consider

those left behind.

The language of demise

My first child was never born—the foetus failed to develop a heart and died.

The doctor assured us that we had nothing to worry about because, in the first

pregnancy, such things happen often—kind of a false start—and the next one

will be perfectly fine for sure. What really struck me then was the discrepancy

in the language. I guess the child occupied the parental realm of the possible,

while the foetus was the clay-cold reality of medicine.

All the things that make me

I am the resultant of all minor and major ailments, injuries, and diseases that have befallen me.

My life consists of all the books I have read or at least hoped to get my hands on, all the places

I have been or refused to go, every word spoken and left unsaid, and many more. But in the end,

nothing of this will reach a graveyard except the name and two random dates. I am an engraver

preparing my tombstone.