I happened. I happened to them just as my birth happened to me.

Inevitably, neither of us were prepared for the many regrets

that come with the territory. No wonder I was too old to be young

and later tried to compensate with a nuclear family of my own.

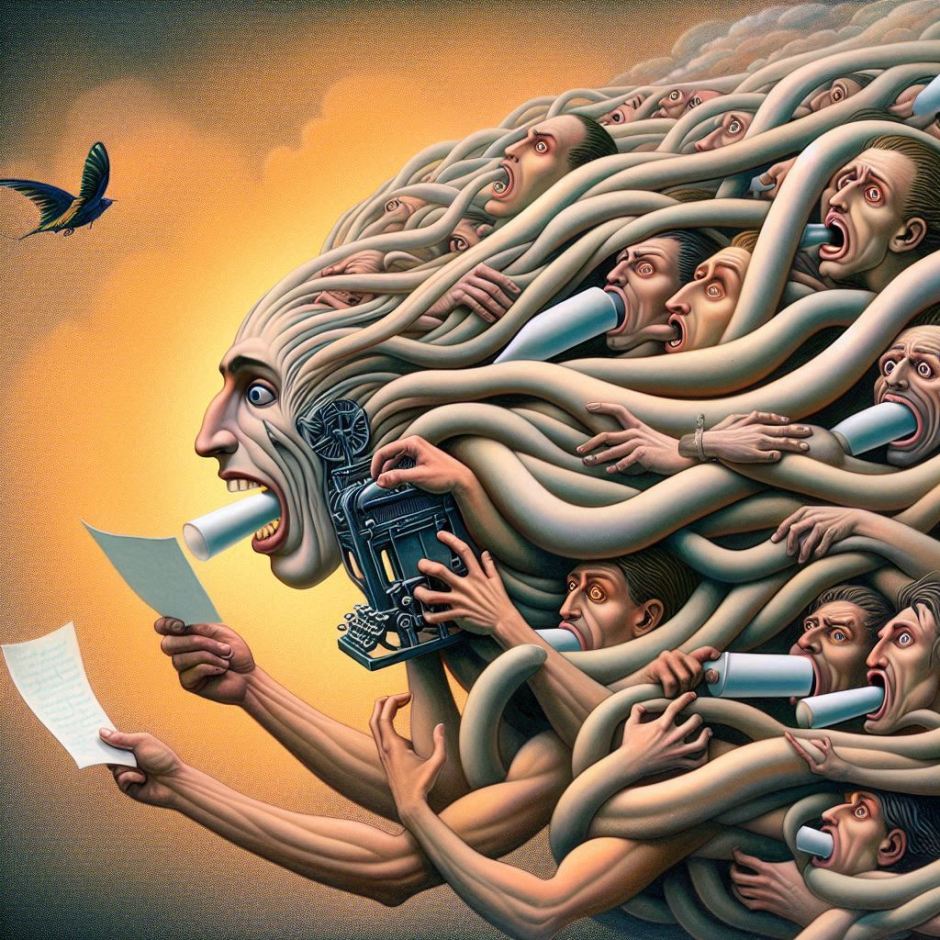

I remember books, lots of books, and the librarian looking at me

with suspicious disbelief as I put another stack on the counter,

so I resorted to a trick, signing up for all the libraries in town.

I wish I had been as cunning with the bullies in the neighbourhood.

Then came puberty, with its teenage acne and masturbation on the couch

under a kitschy reproduction of the Black Madonna of Częstochowa.

I even got a taste of adolescent rebellion—for a whole week or so,

until I got home from boarding school and my father saw my Mohawk.

Adulthood turned out to be not as exciting as I thought it would be.

Well, except for a few acronyms I had to learn along the way

—some we all had to know, even if without much commitment,

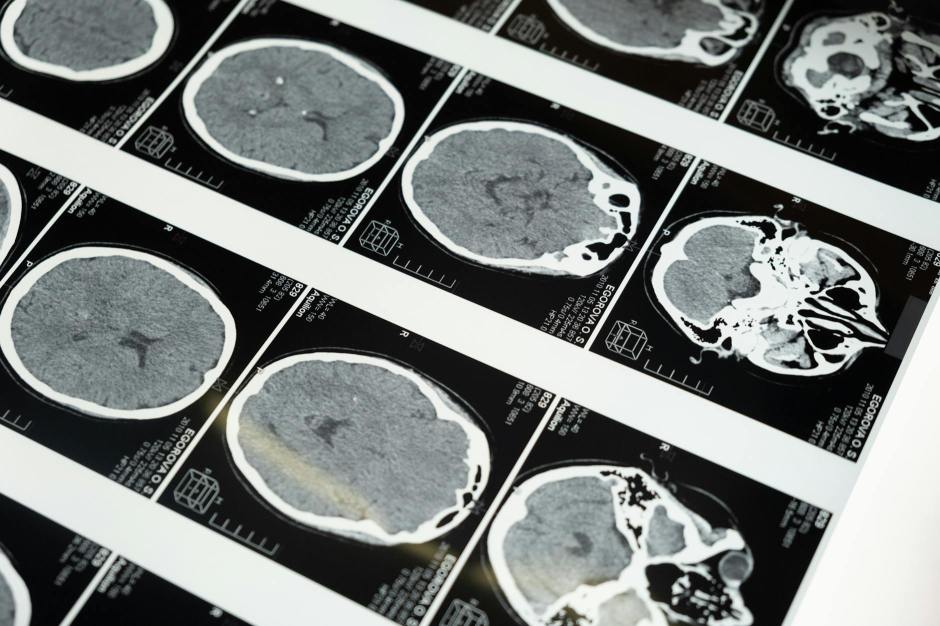

some I experienced first-hand—MRI being the latest.